2018年6月2日

著者:小野 康英(米国特許弁護士)

筆者の私見によれば、米国法の判例は、論点ごとに、大河ドラマの如く、過去から現在までの判例が一連の流れを形成している。このため、過去の判例の検討は、しばしば、今日の判例の趣旨、意義、及び射程の理解に役立つと筆者は考えている。

今回は、米国特許法の歴史において特別の地位を獲得したと考えられる古典的事件を紹介する(電信機事件)。

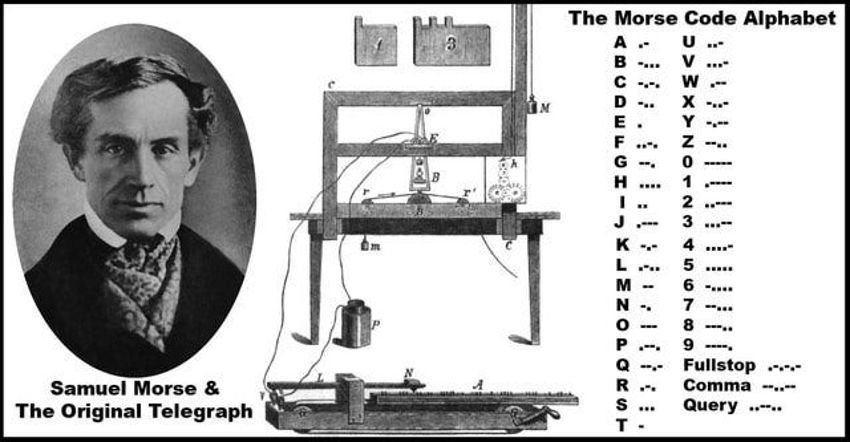

出典:https://www.learning-history.com/samuel-morse/

O'Reilly v. Morse, 56 U.S. (15 How.) 62 (1854)

1.背景

デンマークのOersted(Hans Christian Ørsted)は、1820年、電磁気(electro-magnetism)を発見した。その後程なく、複数の科学者が、互いに離れた地点間における電磁気を用いた情報通信の可能性を探り始めた。しかし、その技術はなかなか実現しなかった。大きな困難は、通信に用いる電流(galvanic current)が、始端でどれだけ大きくても、電線中を伝搬するうちに徐々に強度を下げ、一定距離伝搬すると機械的効果を生じない程度に強度が下がってしまうことであった。その中で、Morse(Samuel F. B. Morse)は、1837年、2以上の電流回路、及び、電磁気力低減防止用の独立電源―所定間隔で設置される継電器(repeater)―の組合せというアイディアを着想した。Morseは、同年から1838年にかけて、その原理に基づく電信装置についての特許出願を行った。そして、2度の再発行出願の末、1848年再発行特許が成立した。Morse の1848年再発行特許(Morse特許)は8つのクレームを含んでいた。本事件で特許有効性が争点となった、Morse特許のClaim 8を以下に示す。

Specification forming part of Letter Patent No. 1,647, dated June 20, 1840; Reissue No. 79, dated January 15, 1846; Reissue No. 117, dated June 13, 1848.

8. I do not propose to limit myself to the specific machinery or parts of machinery described in the foregoing specification and claims; the essence of my invention being the use of the motive power of the electric or galvanic current, which I call "electro-magnetism," however developed for marking or printing intelligible characters, signs, or letters, at any distances, being a new application of that power of which I claim to be the first inventor or discoverer. (Emphasis added)【参考訳】

「8.私は、上記明細書及びクレームに記載された特定の機械又は部品に特許の範囲を限定するつもりはない。私の発明の本質は、任意の距離間での、判読可能な数字、記号又は文字の印付又は印刷のための、私が電磁力と名付ける、電流又はガルバニック電流の動力の使用であり、それがどのように具現化されるかは問わない。私は、その動力の新規の応用の発明者又は発見者であることをここに宣言する。」(強調は筆者)

Morse及びO'Reillyの間のMorse特許をめぐる特許侵害訴訟は、米国最高裁まで争われた。

2.米国最高裁判決

(1)結論

・Morse特許のClaims 1-7は有効。

・O'ReillyはMorse特許のClaims 1-7を侵害する。

・Morse特許のClaim 8は無効。

(2)法廷意見の概要(起草者:Taney主席判事)

(A)有効性

当裁判所は、Morse特許のClaims 1-7の特許有効性に対する無効主張については根拠がないと考える。一方、Claim 8には問題がある。

Claim 8が有効であるならば、どのプロセス又は機械でその結果が達成されるのかは問題でないことになる。我々が知り得ない未来の発明者が、科学の進展の中で、原告明細書が記述するプロセスを一切用いることなく、電流を用いた、任意の距離間での印付又は印刷の技術を発見するかもしれない。

結局のところ、発明者は、Claim 8において、自分が発明をしていないが故に明細書に記述できなかったプロセスの使用について排他権を求めている。当裁判所は、Claim 8は広過ぎ、かつ、特許法上の根拠を欠くと判断する。

もしClaim 8が維持されるとすれば、発明者は、電磁気の動力を用いることにより任意の距離間での識別可能な文字の印刷に成功した、と明細書に記載するだけでよいことになる。当裁判所は、そのような明細書に対して特許を認めることはできないと考える。Claim 8は明細書の開示の範囲を超えている。それにもかかわらずClaim 8に特許有効性を認めるためには、Claim 8の広い文言は十分な記述であり、かつ、その広い文言に対応する広い権利を発明者に認める根拠になるという命題が成り立たなければならない。当裁判所は、特許法をそのようには解釈し得ないと判断する。

(B)侵害論

機械の形状の変更、非本質的構成物品の変更、機械の本質的変更を伴わない公知で等価な動力の使用、動作又は装置配列の変更により、その変更後の機械を新規な発明とすることはできない。その変更後の機械は元の機械に基づく改善と言えるかもしれないが、元の機械の発明者の同意なしにその変更後の機械を使用することは許されない。

O'Reilly'sの電信機は新規な目的を達成するものでも、新規な効果を奏するものでもない。その目的及び効果は、幹線の一端及び途中の継電回路の間の情報の通信である。そして、これは、紙等の媒体に刻印された記号又は文字により達成される。O'Reilly'sの電信機の目的は、Morse教授の電信機と同じである。

O'Reilly'sの電信機は、幹線及び継電回路を用いる点で、Morse教授の電信機と実質的に同一の手段を採用する。よって、O'Reilly'sの電信機はMorse特許を侵害する。

3.私見

(1)有効性

(A)明細書の記述要件(Written Description Requirement)

電信機事件は、明細書の記述要件を争点とする事件とみることができる。現行特許法における記述要件は、基本的に、クレームを支持する記載が明細書に開示されているかどうかを問題とする(35 U.S.C. 112(a))。この点、本事件当時に適用されていた1836年特許法は、クレームを明細書の一部として認知していたが、これを必須記載事項とまではしていなかったと解されている。

Patent Act of 1836, Ch. 357, 5 Stat. 117 (July 4, 1836), Sec. 6.

[B]efore any inventor shall receive a patent for any such new invention or discovery [(as any new and useful art, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement on any art, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter)], he shall deliver a written description of his invention or discovery, and of the manner and process of making, constructing, using, and compounding the same, in such full, clear, and exact terms, avoiding unnecessary prolixity, as to enable any person skilled in the art or science to which it appertains, or with which it is most nearly connected, to make, construct, compound, and use the same; and in case of any machine, he shall fully explain the principle and the several modes in which he has contemplated the application of that principle or character by which it may be distinguished from other inventions; and shall particularly specify and point out the part, improvement, or combination, which he claims as his own invention or discovery. ... (Emphases added)Markman v. Westview Instruments, Inc., 517 U.S. 370 (1996)

Claim practice did not achieve statutory recognition until the passage of the Act of July 4, 1836, ch. 357, § 6, 5 Stat. 119, and inclusion of a claim did not become a statutory requirement until 1870, Act of July 8, 1870, ch. 230, § 26, 16 Stat. 201; see 1 A. Deller, Patent Claims § 4, p. 9 (2d ed.1971). Although, as one historian has observed, as early as 1850 "judges were ... beginning to express more frequently the idea that in seeking to ascertain the invention ‘claimed’ in a patent the inquiry should be limited to interpreting the summary, or ‘claim,’[] "[t]he idea that the claim is just as important if not more important than the description and drawings did not develop until the Act of 1870 or thereabouts." Deller, supra, § 4, at 9. (Emphasis added)

一方、1836年特許法が求める明細書の記述の程度は、規定の文言の近似性に照らすと、現行法が求めるそれと同程度だったと考えられる。その意味で、電信機事件は、明細書の記述要件についての古典的事件と理解することができる。実際、112(a)が実施可能要件(Enablement Requirement)から独立した記述要件を規定するかどうかが争点となったAriad Pharm. (Fed. Cir. 2010) (en banc)(現時点における明細書の記述要件の基本判例)では、複数の判事が、本事件を引用しつつ、各自の持論を展開した。

Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Eli Lilly and Co., 598 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (en banc), Footnote 4

Morse, decided under the 1836 Act, can also be interpreted as involving a separate written description inquiry. 56 U.S. (15 How.) 62, 14 L.Ed. 601. The patent at issue contained eight claims, only seven of which recited the specific instrumentalities of the telegraph developed by Morse. The eighth claim, in contrast, claimed every conceivable way of printing intelligible characters at a distance by the use of an electric or galvanic current. Id. at 112. The Court rejected the latter claim as too broad because Morse claimed "an exclusive right to use a manner and process which he has not described and indeed had not invented, and therefore could not describe when he obtained his patent." Id. at 113 (emphasis added). Such a rejection implies a distinct requirement for a description of the invention. Yet, in reaching its conclusion, the Court also detailed how the claim covered inventions not yet made, indicating the additional failure of the description to enable such a broad claim. See id. at 113–14.Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Eli Lilly and Co., 598 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (en banc), additional views by NEWMAN, Circuit Judge.

The written description is the way by which the scientific/technologic information embodied in patented inventions is disseminated to the public, for addition to the body of knowledge and for use in further understanding and advance. See [Capon v. Eshhar, 418 F.3d 1349] at 1357 ("The written description requirement thus satisfies the policy premises of the law, whereby the inventor’s technical/scientific advance is added to the body of knowledge, as consideration for the grant of patent exclusivity."). This accords with long-standing principles, as in the classical case of O’Reilly v. Morse, 56 U.S. (15 How.) 62, 14 L.Ed. 601 (1853), where the Court approved Samuel Morse’s claims based on the system of current boosters that achieved his long-distance communication called the telegraph, but denied his claims for this use of an electric current "however developed." Id. at 113. As the court debates the relationship between "written description" and "enablement," let us not lose sight of the purpose of Section 112.Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Eli Lilly and Co., 598 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (en banc), dissenting-in-part and concurring-in-part opinion by LINN, Circuit Judge.

The majority also rests on O’Reilly v. Morse, 56 U.S. (15 How.) 62, 120, 14 L.Ed. 601 (1854), where the Supreme Court invalidated one of Samuel Morse's telegraphy-related claims for claiming “what he has not described.” Maj. Op. at 1346 n.4. Lilly cites passages from Morse and highlights every instance of the words “description” or “described.” Lilly’s Br. 8. However, this places too much stock in these words and assumes that "describes" meant in 1854 what the majority would like it to mean today. Morse’s description was deficient because it did not enable the full scope of his broadest claim (to all possible electrical telegraphs), not because it failed the equivalent of a present-day "possession" test for written description.

(B)機能表現クレーム(MPF claim: Means-Plus-Function Claim)

電信機事件において、Morseは、Claim 8に"a new application of [the motive power of the electric or galvanic current[], however developed for marking or printing intelligible characters, signs, or letters, at any distances]"と規定していた。Claim 8は、構造、材料又は行為を規定する代わりに、特定の機能を実行する手段又は工程の形で表現された構成要素を含むクレーム、すなわち、機能表現クレームと理解することができる。本事件において、米国最高裁は、クレームの記載が明細書の開示の範囲を超えていることを理由にClaim 8を無効と判断した。その後、米国最高裁は、Halliburton事件(1946年)において、本事件を引用した上で、機能表現クレームの使用自体を否定した。

Halliburton Oil Well Cementing Co. v. Walker, 329 U.S. 1 (1946)

The Halliburton device, alleged to infringe, employs an electric filter for this purpose. In this age of technological development there may be many other devices beyond our present information or indeed our imagination which will perform that function and yet fit these claims. And unless frightened from the course of experimentation by broad functional claims like these, inventive genius may evolve many more devices to accomplish the same purpose. See ... O’Reilly et al. v. Morse et al., 15 How. 62, 112, 113, 14 L.Ed. 601. Yet if Walker’s blanket claims be valid, no device to clarify echo waves, now known or hereafter invented, whether the device be an actual equivalent of Walker’s ingredient or not, could be used in a combination such as this, during the life of Walker’s patent.

米国議会は、Halliburton事件から6年後、1952年特許法(現行特許法)を制定し、第112条第3項を新設することにより、Halliburton事件を立法的に覆した。当時の第112条第3項と内容の同一性を保つ現行第112条(f)項は、以下のとおり規定されている。

35 U.S.C. 112 Specification.

(f) ELEMENT IN CLAIM FOR A COMBINATION.—An element in a claim for a combination may be expressed as a means or step for performing a specified function without the recital of structure, material, or acts in support thereof, and such claim shall be construed to cover the corresponding structure, material, or acts described in the specification and equivalents thereof.【参考訳】

(f)組合せに係るクレームの構成要素―組合せに係るクレームの構成要素は、その構造、材料又は行為を規定することなく、特定の機能を実行する手段又は工程の形に表現することができる。そのクレームは、明細書に記載された対応する構造、材料又は行為、及びその均等物を権利範囲に含むと解釈する。

以上の経緯を踏まえると、電信機事件は、機能表現クレームに関係する判例の源流と解する余地がある。

(C)特許主題適格性(Subject Matter Eligibility)

筆者の見解では、電信機事件は、特許主題適格性(35 U.S.C. 101)が争点となった事件ではない。しかしなぜか、特許主題適格性の主要判例は、しばしば、本事件を引用して、特許主題適格性を論じている。

Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U.S. 66 (2012)

"The Court has long held that this provision contains an important implicit exception. "[L]aws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas" are not patentable. []O'Reilly v. Morse, 15 How. 62, 112–120, 14 L.Ed. 601 (1854)[].""Further support for the view that simply appending conventional steps, specified at a high level of generality, to laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas cannot make those laws, phenomena, and ideas patentable is provided in O'Reilly v. Morse, 15 How. 62, 114–115, 14 L.Ed. 601[]."

McRO, Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games America Inc., 837 F.3d 1299 (2016)

"The abstract idea exception prevents patenting a result where "it matters not by what process or machinery the result is accomplished." O'Reilly v. Morse, 56 U.S. (15 How.) 62, 113, 14 L.Ed. 601 (1854).""The abstract idea exception has been applied to prevent patenting of claims that abstractly cover results where "it matters not by what process or machinery the result is accomplished." Morse, 56 U.S. at 113."

"By incorporating the specific features of the rules as claim limitations, claim 1 is limited to a specific process for automatically animating characters using particular information and techniques and does not preempt approaches that use rules of a different structure or different techniques. See Morse, 56 U.S. at 113."

一般的に、特許主題適格性は「発明の本質の抽象性」を問題とするのに対し、明細書の記述要件は「明細書の記載の抽象性」を問題とする。よって、両者の「抽象性」は意味が異なると考えられる。しかし、1836年特許法において、特許主題適格性及び明細書の記述要件はいずれも第6条に規定されていることを勘案し、及び、論点を上位概念化すれば、本事件は「抽象性」を議論していると言うこともできるので(かなり無理している感は否めないが)、特許主題適格性を争点とする事件において本事件を引用する判例があるのかもしれない。

Patent Act of 1836, Ch. 357, 5 Stat. 117 (July 4, 1836), Sec. 6.

[A]ny person or persons having discovered or invented any new and useful art, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement on any art, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, not known or used by others before his or their discovery or invention thereof, and not, at the time of his application for a patent, in public use or on sale, with his consent or allowance, as the inventor or discoverer; and shall desire to obtain an exclusive property therein, may make application in writing to the Commissioner of Patents, expressing such desire, and the Commissioner, on due proceedings had, may grant a patent therefor. But before any inventor shall receive a patent for any such new invention or discovery, he shall deliver a written description of his invention or discovery, and of the manner and process of making, constructing, using, and compounding the same, in such full, clear, and exact terms, avoiding unnecessary prolixity, as to enable any person skilled in the art or science to which it appertains, or with which it is most nearly connected, to make, construct, compound, and use the same; and in case of any machine, he shall fully explain the principle and the several modes in which he has contemplated the application of that principle or character by which it may be distinguished from other inventions; and shall particularly specify and point out the part, improvement, or combination, which he claims as his own invention or discovery. ... (Emphases added)Finjan, Inc. v. Blue Coat Systems, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2018) (Dyk, J.) (Case No. 2016-2520; January 10, 2018)

Apple, Affinity Labs, and other similar cases hearken back to a foundational patent law principle: that a result, even an innovative result, is not itself patentable. See Corning v. Burden, 56 U.S. 252, 268 (1853) (explaining that patents are granted “for the discovery or invention of some practicable method or means of producing a beneficial result or effect . . . and not for the result or effect itself”); O’Reilly v. Morse, 56 U.S. 62, 112–113 (1853) (invalidating a claim that purported to cover all uses of electromagnetism for which “the result is the making or printing intelligible characters, signs, or letters at a distance” as “too broad, and not warranted by law”). (Emphasis added)

(2)侵害論

米国最高裁は、侵害論において、クレームの各構成要件を被疑侵害製品の各構成要件と対比する代わりに、両者の発明としての共通点を検討し、文言侵害及び均等論侵害の議論を混在させる形で、被疑侵害製品の権利侵害の結論を導いているように見受けられる。その論理展開は、中心限定主義(central definition)を基調としつつも、均等論又はそれに近似する論理を持ち出すあたり、周辺限定主義(peripheral definition)の考え方も含まれている。

いずれにしても、本事件における米国最高裁の侵害成否判断は、現行特許法における侵害成否判断とは異なっていると思われる。本事件における侵害成否判断の手法が後の判例において引用されることは皆無である(又は、筆者はそのような判例を寡聞にして知らない)。

吉藤幸朔(著)、熊谷健一(補訂)「特許法概説〔第13版〕」有斐閣(1998年)、VII. 特許権 3. 特許権侵害、脚注(530頁)

「1)中心限定主義[:]一般に、特許請求の範囲の記載に必ずしも拘泥することなく、これを核としてその外方に一定の広がりの技術的範囲を認めていく(核以下に縮小解釈することはしない)解釈の仕方を、講学上、中心限定主義(central definition)という。ドイツはその代表的な国とされてきた。一般的発明思想は、中心限定主義の最も特徴的ないし徹底した考え方を示すものであるということができよう。2)周辺限定主義[:]中心限定主義に対し、特許請求の範囲の記載によって定められる区域を、原則として技術的範囲の最大限とし、例外として、当該区域と実質上同一と認められる範囲の至近範囲の拡張を認める(均等論)ことがあるが、むしろ逆に当該区域よりも狭い範囲に縮小解釈すること(逆均等論)*がある解釈の仕方を講学上、周辺限定主義(peripheral definition)という。アメリカはその代表的な国とされてきた(しかし 、1980 年代中頃からの考え方は、周辺限定主義よりもむしろ中心限定主義に近いということもできるようである[])。

* 逆均等論(reverse doctorine [sic] of equivalents)

発明の実質的保護のために拡張解釈をする均等論の解釈手法が、逆に、第三者保護のために縮小解釈をするのに用いられるので、逆均等論と称される。わが国における出願の経過参酌の原則[]、実施例要旨説[]等と趣旨を同じくするものであるということができる。」

Samuel F. B. Morse (1791 – 1872)は、電信機事件によりモールス電信機の発明者として認められ、かつ、電信機の実用化に尽力したことで、米国産業界の歴史に名を残した。また、本事件において、Morse は、Claims 1-7に基づき、Morse特許の行使に成功した。

一方、電信機事件は、米国特許法の歴史において、無効と判断されたClaim 8についての議論に関連して、米国特許法の重要論点(具体的には、明細書の記述要件、機能表現クレーム及び特許主題適格性)についての判例の源流という特別の地位を獲得したと考えられる。

Next>>第9回:米国特許法の歴史~電話機事件(The Telephone Case)~

Previous<<第7回:米国特許法の用語~Reverse v. Vacate~